Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord in the Press

In Kristina Wong’s ‘Sweatshop’ world, buckle up for a wild pandemic ride at La Jolla Playhouse

Koreatown resident’s solo play about running an army of face mask-sewing volunteers was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Drama

By Pam Kragen

September 26, 2022

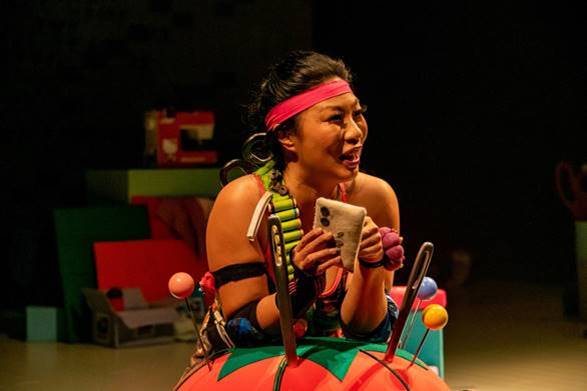

Kristina Wong in La Jolla Playhouse’s West Coast premiere of Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord.(Courtesy of Jenna Selby)

Performance artist Kristina Wong’s latest solo play, “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord,” seems straightforward at the outset.

Before her 90-minute comedy even begins, she has quietly taken a seat at center stage behind her Hello Kitty sewing machine, speed-stitching cloth face masks amongst a sea of massively oversized pincushions, bolts of fabric and spools of thread designed by Junghyun Georgia Lee. But within minutes, the Los Angeles actor’s battle against the spread of COVID has mushroomed into an all-out war against self-doubt, racism, medical misinformation, political fascism and her own life choices.

The play, which opened Saturday in its West Coast premiere at La Jolla Playhouse’s Potiker Theatre, was named a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It chronicles Wong’s pandemic-fueled project, where over 504 days, she created and marshalled a volunteer army of nearly 800 sewing enthusiasts nationwide. Together they sewed and shipped more than 350,000 face masks and distributed several hundred thousand more pieces of personal protection equipment, primarily to marginalized populations in low-income communities, prisons, Indian reservations, homeless encampments and at the border.

Told in chronological fashion in a lively, fast-paced and very funny, audience-interactive production directed by Chay Yew, Wong explains how her mask project got its humble start on March 20, 2020. Out of work and doom-scrolling on Facebook in her Koreatown apartment in Los Angeles, Wong read about hospital workers pleading for face masks and she decided to put her own, not insignificant, sewing skills to work (she sews many of the props used in her shows, including the oversize felt iPad and cellphone in “Sweatshop Overlord”). Then she gradually assembles her troops — which she dubbed the Auntie Sewing Squad, ASS for short — who would grow to include her mom and a generous “auntie” named Sally, who wouldn’t survive the pandemic.

Decked out for war by costume designer Linda Cho, Wong carries face mask-shooting guns and wears a bandolier of thread spools, a giant pair of scissors strapped kitana-style to her back and pincushion armbands. She talks about battling fear, illness and fatigue, discovering her previously untapped wells of empathy and maternal skills, and how she made undercover deals for muscle-soothing CBD pills and ever-elusive elastic for the masks.

In one of the show’s best bits on opening night, Wong asks the audience to donate their excess elastic to the cause and within moments, scrunchies, hairbands and, yes, bras, were sailing through the air toward the stage. Projection designed by Caite Hevner spotlights the many lows of the past two and a half years, including the murder of George Floyd, anti-Asian attacks, anti-mask rallies and the Jan. 6 insurrection, all of which Wong touches on with a mix of seriousness and humor.

Following the arrival of vaccines and cheap masks in stores, ASS disbanded on Sept. 25, 2021, but Wong says this group of selfless aunties — which Wong said is a nice word for old “spinsters” like herself — remain devoted to one another. Early in the play, Wong questions her decision of choosing the solitary life of an artist over starting a family. But through her sewing squad, she ended up with hundreds of new chosen family members.

Read at The San Diego Union-Tribune

Performance artist Kristina Wong joins host Dave Drexler to preview “Kristina Wong: Sweatshop Overlord” at La Jolla Playhouse (Sep. 20-Oct. 16)

Program: Inside Art

Air Date: 9/25/2022

Kristina Wong is not invisible

By Julia Dixon Evans

September 21, 2022

Playwright, comedian, performer and Pulitzer Prize finalist Kristina Wong is shown in an undated photo. Photo by Tom Fowler.

The early days of the COVID-19 lockdowns and quarantines brought total upheaval to life as we knew it. Alongside the tragedy unfolding around us, some of us spent the early days of the pandemic trying our hand at sewing cloth masks. Comedian, playwright, and performer Kristina Wong draws on those times in a new play. Named as a finalist for a Pulitzer Prize in theater, “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord” is a solo show about the group of individuals Wong assembled across the country to make homemade masks to meet the urgent demand.

The play explores lockdowns, Asian American racism, Facebook groups, friendship, invisible labor and generosity.

Preview performances begin Tuesday, Sept. 20, at La Jolla Playhouse, and it officially opens on Saturday and runs through Oct. 16, 2022. Playwright, comedian and performer Kristina Wong spoke with KPBS Arts producer and editor Julia Dixon Evans, their conversation below had been lightly edited for clarity.

Read More

This play was inspired by your own reality in the early days of the pandemic when masks were hard to come by. Can you walk us through what that time was like for you?

Wong: Yes. I was actually all set to tour another show called “Kristina Wong for Public Office.” In that particular show, I spent years researching running for office and created this whole live rally that was going to tour up until the 2020 November election. Like, I’m shaking hands, I’m in people’s faces, and suddenly I’m deemed non-essential, as all artists are, and I’m home in my underwear in Koreatown trying to figure out what to do because I was getting emails that shows are canceled, stay inside.

I sew my sets and props — that’s sort of a signature of my work. I’ve never made medical equipment before, but I was tagged in an article saying that hospitals were looking for home-sewn masks. And I had this whole “aha” moment of: I’m going to sew masks. I’m going to become essential. I made a very naïve offer to Facebook and Instagram saying, If you need a mask and you’re an essential worker or immunocompromised, let me help you — not realizing that everyone who’s been avoiding seeing my shows for years would just come out of the darkness, find me and ask for a mask.

So I was overwhelmed with what seemed like a crazy number, like around 200 mask requests at that point, about four days in and was like, I need to get help. I can’t do this by myself. And it’s also just really hard to find materials right now because stores are closed and the stores that are open are sold out of elastic and cotton fabric. So I started a Facebook sewing group thinking, okay, this is just for three weeks until the cargo ships from China show up with masks and the government distributes these masks. I call the group “Aunties Sewing Squad.” I name it in such a rush, I don’t realize that our acronym is A-S-S.

And I end up having to lead this group. It’s not like you just start a Facebook group and the masks just show up, but there’s a lot of organizing and leadership that needs to happen. And it became clear this is not just hospitals, but there are these communities in rural areas, farm workers, indigenous communities that need these masks. So we ended up becoming a 17-month-effort, and we were doing everything from relief vans to the Navajo Nation, winter coat drives to the Lakota Reservation, sending a lot of supplies to the border, to migrants who are arriving. And we became a network of 800 volunteer aunties across 33 states. That’s what I did during my pandemic. That’s the story of this show.

At what point did you realize that you had to make theater out of that moment?

Wong: About one month into this, people kept saying, this is going to be your next show, isn’t it? I’m like, we don’t even know if there’s ever going to be theater again. We don’t even know if there’s going to be civilization. This is the last thing I’m thinking about, is how to make this funny. But it became so clear that what I feel like we were witnessing was — it was the strangest war where instead of soldiers, I had a battalion of aunties. And instead of machine guns, we had sewing machines, and instead of bullets, we had fabric and thread and elastic, right? And it just felt like the things I was witnessing and that the other aunties were witnessing of this pandemic, from the proximity of being someone who we have these skills that were passed down that could save someone’s lives, it was just sort of incredible.

But also, I think what I was witnessing was a very specific generosity. And I think for some people who couldn’t understand that, that’s why I wanted to make a show, is to really show them there’s this moment in our history that was awful, but what I saw in this moment was this incredible generosity.

I have friendships with people — I’ve not even met them in person yet, but I feel so much love and respect for them because they were willing to basically put their own health at risk. Going to the post office, picking up materials, sewing into the night to protect people they’d never met before. And that sort of reality, that sort of invisible labor that is sewing, I really wanted to put meaning to.

And I also really wanted to show that in this moment where people are so angry at Asian Americans because they think that somehow we brought this virus here, that there are all these Asian Americans who are actually stepping up and trying to protect frontline workers, trying to keep this country safe. So for me, that’s when it became very clear that there was probably a show here because we were living an experience that was very different than maybe a lot of people who were using the time to catch up on Netflix or going through divorces — some of our Aunties went through divorces. But it just was so specific and so worth sharing.

This is a play that’s also about family, particularly women. What did you want to explore with those relationships and friendships — and these generational bonds when it comes to skills like this, like sewing?

Wong: I think when we think of heroes or we think of people who are out to protect us, we think like big, strong, burly men with guns. And there is all this caretaking that happens among aunties. And to me, I love the term auntie, at least at this age in my life, because I don’t have children, I’m not married, and it sure beats words like spinster or old maid to be called auntie by people. It’s a term of respect. And that was sort of the gift of naming this group in a rush “Auntie Sewing Squad” — is there was so much pride in being called an auntie and so much of a sweetness, I could order people around, go “Aunties, I need you to sew faster. Please, aunties,” versus “Hey, volunteers, keep sewing,” right? There’s something much sweeter and familial about that.

And these are the years of the pandemic, that these are the last of my fertile years. And it became clear like, oh, I’m not going to have children, at least biological children. And that’s it. This is it. But what I really learned was I have this family, I have relationships that are close and meaningful in ways that I don’t think I need a biological family to have. I really learned connection in this way. I still don’t even know what half the aunties do for a living. And I think that’s incredible because when you live in Los Angeles, you usually meet people based on what their career is first. And so it was so incredible to meet people on the level of what they had to give.

It’s widely believed that messaging from former President Donald Trump led to waves of racism, hate crimes, violence towards Asian Americans, like specifically his use of the term “China virus.” I’m wondering how you approach this in the play.

Wong: So here’s this terrible irony, exactly one year from when we started sewing masks, March 2020 to March 2021, the Atlanta Spa massacre happened. And it went from aunties were protecting the world with masks to we were then distributing self-defense weapons to the Asian aunties. We usually had care items like baked goods and things like this. And suddenly we’re distributing kubotans, hand alarms, and sharing links to self defense classes on Zoom. And it felt like, okay, the pandemic might be subsiding, but this racial pandemic is not. And we’re sort of left in the aftermath of finding a way, of having to forge a new sense of protection. So that’s sort of one arc that I go through in it. And this sort of terrible irony of having to go from defender to defendee.

But for me, this show is also that defense, right? Because I feel like Asian Americans are so invisible and this labor is so invisible. And the way people would regard our labor. For the most part, people were very grateful for our sewing, but there are moments where people would talk to us like we were just Amazon Prime, like, I want 20 masks that looks like this. And I’m like, “We’re in a pandemic. Stores are not open. I cannot customize masks for you right now. I don’t do this professionally.” And there are interactions we had that were so transactional.

And I feel like so much of me wanting to do the show was to put a face on this labor. And really show just how hard this was, not because we’re more important than anybody else, but I think that it’s important in this moment to understand that we weren’t just sitting on our hands and doing nothing. Here’s where a lot of Asian Americans were stepping up.

Performance Artist Kristina Wong Riding High as a ‘Sweatshop Overlord’ and Pulitzer Prize Finalist

In a funny and candid interview, the Los Angeles resident talks about how her pandemic-born hobby turned into a nationally acclaimed play

By Pam Kragen

September 18, 2022

Kristina Wong, costumed for her solo play “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord,” plays Sept. 20-Oct. 16 at La Jolla Playhouse. Photo by Tom Fowler.

In mid-March 2020, performance artist-playwright Kristina Wong was midway through the second live show of a national tour when all of the students in the college auditorium where she was performing received a simultaneous text that the campus would shut down the next day due to COVID-19.

With the tour canceled and all theaters closed, Wong found herself quarantined in her L.A. Koreatown apartment with nothing to do but watch and read the news about the fast-growing pandemic. Then a friend tagged Wong on a social media post about how local hospitals were in need of face masks and she found a way to become an essential worker.

“The curse of the artist is that when push comes to shove, no one wants to watch your play,” she said. “But I sewed my own set pieces and props and I’d sewn myself a big vagina costume. I never imagined these skills could help anyone.”

So that day, with a few scraps of fabric, some bad elastic and her Hello Kitty sewing machine, Wong sewed herself a face mask, and on March 20 she posted on Facebook that she was taking requests for more. That was the beginning of Wong’s Auntie Sewing Squad (ASS for short), a nationwide network of nearly 800 volunteers who over the next 17 months would make and distribute nearly 400,000 masks as well as hundreds of thousands of other medical supplies to farmworkers, Indian reservations, immigrants at the border and more.

That was also the inspiration for Wong’s latest solo play, “Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord,” which premiered last fall in New York and was a finalist for the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for Drama. It opens Tuesday at La Jolla Playhouse.

Read More

Performance artist Kristina Wong poses in March 2021 in the sewing room of her apartment in Koreatown, Los Angeles, when she was leading the Auntie Sewing Squad Facebook group that sewed masks for those who needed them. (Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times)

Wong, 44, recently spoke with the Union-Tribune about how she spent the pandemic, how the experience changed her life and what it feels like to be the first Asian American woman finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for Drama.

Q: Congratulations on your Pulitzer honor. What did it feel like when you got the news?

A: I’m still amazed by it. To be in that company … Tennessee Williams, Thornton Wilder and Kristina Wong? It’s so unreal. Six years ago, my best friend Brian Feldman, who’s also a performance artist, and I submitted our plays for the Pulitzer as a joke, because anyone can, and we could say we were “contenders.” Just the idea of being so close to it was exciting. I got my press pass and prepared three speeches for if I won, lost or was a finalist, but I lost to a play called ‘Hamilton.’ I ended up reading all three speeches on a livestream. My acceptance speech was like ‘Screw you, Lin-Manuel.’ When I revisited those speeches after becoming a real-life finalist it was so strange. So much of my life is a joke.”

Q: How did mask-making mushroom from just you into a Facebook group project?

A: Four days after I posted online that I could make masks for people, apparently all the people who had been avoiding seeing my theater shows were able to find me on the Internet and ask me for a mask. I kept saying yes. I overpromised the Internet and I needed to find some people to come help me so we could fill the requests and I could quietly go away.

Q: How did you become a “sweatshop overlord”?

A: The moniker ‘Sweatshop Overlord’ came from me, a few days into the process, when I said to the friends in my group ‘I’m running a sweatshop’ and that became my nickname. When summer schools got canceled during the pandemic, I made a joke to parents that instead of summer school your children can learn to work heavy machinery and make medical equipment. I made child labor a joke, but it became a reality.

Q: How was the “Auntie Sewing Squad” born and what’s an “Auntie”?

A: When I was trying to figure out what to do, I looked on Facebook and found all these existing mask-making groups that were serious. I didn’t want to imply any professionalism was needed. This was going to be a little thing. It wasn’t until later someone told me about the ASS acronym. That was unintentional humor. An Auntie is a term of respect. I’m getting called an Auntie more and more. It’s a nicer word for spinster, old maid or unmarried woman.

Q: What was it like meeting these women from all over the country and sharing this mission with them?

A: I now have a family all over the country and half of them I’ve never met before. With how scary it felt at times, we bonded the way soldiers bond. When you meet someone else who’s willing to sacrifice so much in a moment for people they don’t know, they become family.

Q: How did your work running the Auntie Sewing Squad become a play?

A: It started as a freeform Zoom piece from my bedroom, about a month into the Sewing Squad, where I was developing it at that point. The screen would flash “Day 13″ and I’d say where we were at. It was like I was witnessing a war. New York Theatre Workshop opened it off Broadway last October. It ran for four weeks and was a New York Times Critics Pick. This will be the West Coast premiere, and from here I go on to Portland Center Stage (in Oregon) and then to the Center Theatre Group in L.A.

Q: For your last performance art piece, “Kristina Wong for Public Office,” you ran a campaign and wrote about the experience. Today, you’re an elected representative of Wilshire Center Koreatown Sub-district 5 Neighborhood Council. How does being a politician compare to being an artist and sweatshop overlord?

A: I really have been frustrated with elected office. In the pandemic, we had to postpone meetings for a few months. Artists can just get things done faster. I’m very proud of how we came together. A lot of my background as an artist did show up. Most of the folks who were our Super Aunties were artists. We are an example of what it would look like if a bunch of artists ran FEMA. We’re creative and resourceful. The question I ask in the play is am I more effective as a politician or an artist? I feel it’s a combination of the two. Artists are necessary to shift the culture, which is the force that eventually shifts legislation. Artists should still run for office. It’s a big pain and it’s a lot of sifting through garbage, but it has its rewards.

Q: Did the Auntie Sewing Squad experience change how you see yourself?

A: I never saw myself as a leader. The joke in the show is I do solo performance because I don’t drink the Kool-Aid, I serve it. I tend to prefer to work alone so it was weird that I was in this situation where I was having to deal with all these personalities and manage all these emotions. It was a strange time, but I did what had to be done. I thought I’d be the one who panicked in the situation, but it was this moment of chaos where if you showed any inkling you had any idea what to do, people would gravitate to you. I joke that I’m this self-absorbed performance artist, and it turned out I had empathy. A theme in a lot of my shows is that I’m this martyr named Kristina Wong who embarks on these crazy ideas to help people and get way deep in. This one was one of those, too, but I felt like I could not give up.

‘Kristina Wong, Sweatshop Overlord’

When: Opens Tuesday and runs through Oct. 16. 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays and Wednesdays. 8 p.m. Thursdays and Fridays. 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays. 2 and 7 p.m. Sundays.

Where: Potiker Theatre, La Jolla Playhouse, 2910 La Jolla Village Drive, UC San Diego Theater District, La Jolla

Tickets: $25 to $00

Phone: (858) 550-1010

Online: lajollaplayhouse.org

Read at The San Diego Union-Tribune