Trails and Paths Along the Coast Starlight

Playwright Keith Bunin talks with dramaturg Shirley Fishman about his journey from child actor to the inspiration for his new play – being a passenger on an iconic California train trip

SF: When did you start to write plays?

KB: I started writing before I could read. I would tell stories to my mother and she’d write them down in little handmade books that I would illustrate. She was a teacher, very arts-oriented and encouraging that way. Writing was always so natural for me that I never thought it was particularly special.

SF: Were you involved in theatre when you were a child?

KB: Oh, yeah, I was a theatre kid. I went to a children’s theatre school for two hours every Saturday in Poughkeepsie, where I grew up and where my dad was a manager at IBM. I had this amazing teacher, Jan Denison, an IBM wife who was bored and started a children’s school with other IBM wives. She directed children’s theatre plays and I acted in them. She worked in a way that emphasized theatre as a means of creative expression and communication that was organic and student based. I loved it! Being a kid actor is a very doable way of being a part of the theatre.

In my sophomore year of high school I got a scholarship to attend a Quaker school in my hometown. I had an amazing teacher there named Niyonu Spann. She was my advisor, was a fantastic musician and directed musicals at the school. She was a very spiritual person; she really made me think deeply about my personal and moral responsibility as an artist.

Even today, in terms of my philosophy and how I approach what I do, I owe an enormous amount to those two women.

SF: Where did you go to college?

KB: I went to NYU Film School. I was majoring in film production, but I pretty quickly realized that the problems I was most interested in solving were writing problems. So little by little everything else fell away and I finally accepted that I was a writer.

While I was in college, I started a theatre company in the city with some friends and was writing plays and screenplays at the same time. When I graduated, it was a good time to be a young screenwriter in New York. Miramax Films was based in New York and they were at the height of their success with films like Pulp Fiction and Shakespeare in Love. Other film companies began to set up shop in the city and I got some screenwriting jobs. I got hired because I was willing to work for cheap. So I wrote plays and screenplays and earned a decent living with part-time jobs here and there. Within a few years I was able to fully support myself with my screenwriting and write plays.

SF: In 2012 your play Sam Bendrix at the Bon Soir was produced off-site at Martinis Above Fourth as part of our Without Walls program. Then the Playhouse offered you a commission for a new play. Did you have an idea of what you wanted to write about?

KB: I knew I wanted to do a story about California and the West. You and I are both East Coast people and we’re fascinated by California – the native people, the settlers – why they came, and the trails and paths they took to get here. The stories of their journeys made me think about what it takes to be a pioneer.

In 2014 I took a film job in the San Francisco Bay Area. The original contract was for twelve weeks; I ended up staying on that job for three years. Although I had spent a few weeks or months in California here and there, I had lived in New York my whole life. As a writer you become accustomed to solitude; on this job it was the complete opposite. The film project was extremely collaborative, so work was incredibly social. But I didn’t know a lot of people in the Bay Area outside of work, and I decided that I’d make an effort to see as much of the West Coast as possible.

SF: How did you arrive at writing about a train trip?

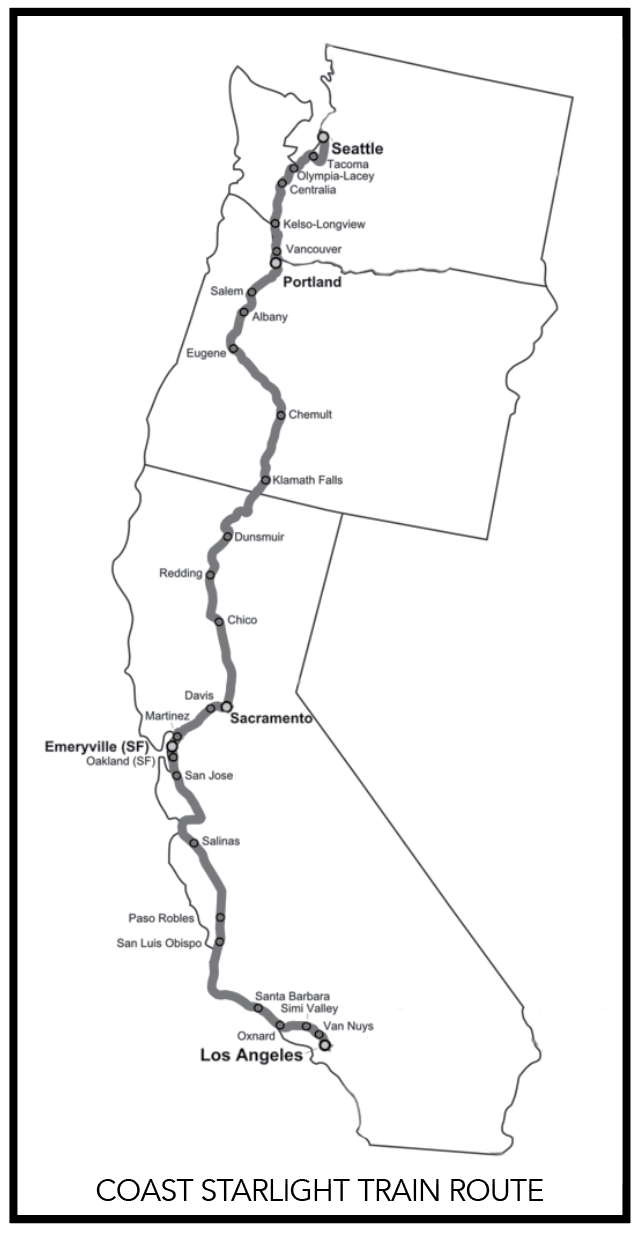

KB: When I first arrived in San Francisco, I stayed in an East Bay residential hotel, the Hyatt House in Emeryville, which was literally next door to the Amtrak station. Two long-distance trains stop in Emeryville every day – the Coast Starlight, a 36-hour trip from Los Angeles to Seattle, and the California Zephyr to Chicago. One weekend soon after I got to Emeryville, I went to visit a friend of mine who was performing at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. I took the Coast Starlight from Emeryville to Klamath Falls, rented a car and drove to Ashland. It was one of the most beautiful trips I’d ever taken. Over the next few years, I took the Coast Starlight both north and south.

While I was in the Bay Area, I visited City Lights and other bookstores, visited the Oakland Museum of California and the Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles. It had an exhibit about the history of jackrabbit homesteads that I wrote into the play. Because I was traveling so much, I did a lot of reading. I read and re-read John Steinbeck, Jack Kerouac and Joan Didion, and was impacted by their incredibly different views of California. I also read Lucia Berlin, a Raymond Carver-style short story writer who wrote about Northern California.

SF: In thinking about who would be at the center of your play, what inspired the character of TJ?

KB: The idea of writing about a Navy medic came from the time I spent rehearsing Sam Bendrix at Martinis Above Fourth. A number of the bartenders who worked there were veterans, and I got to know them pretty well. They’d come from all over the country, had very different military backgrounds and tremendously varied political beliefs. But they’d all been profoundly affected by their service. It made me think on a deeply personal level about what our responsibilities are to the people who fight for us. The story of TJ came into focus – a young man in the military service with a problem.

SF: What about the passengers on the train?

KB: Traveling alone, I was among strangers a lot. When we travel, the other passengers appear to us as figures in a landscape. But on a long trip, they become alive in our imaginations. We begin to form a relationship to them and we affect one another in a granular way. I started thinking about TJ. He has a problem, he’s on a train among strangers and he can’t speak to anyone about it. Once I intuitively understood how this could work theatrically, I had the structure and the story – six characters getting on the train at various stops along the Coast Starlight route. Each of them is in a moment of real crisis, and even though they barely speak to each other, they find themselves communicating on a deeper, subconscious level.

SF: How did you imagine it would work?

KB: In a book you can easily enter a character’s subconscious, but it’s usually a selective omniscience. In a film, that sort of thing gets literal very quickly. In theatre there’s a way to dramatize an experience we’ve all had when we’re traveling – the one in which we can feel entirely solitary and at the same time be part of a community of fellow travelers. I asked myself, what if my play existed in a shared space where the passengers communicate with each other, even if they don’t speak to each other.

SF: You said that the characters in The Coast Starlight had a “collective subconscious.” What did you mean by that?

KB: When you’re on a train or bus or subway, you sometimes become conscious of someone across the aisle and begin imagining their lives. It’s a natural thing that we all do. In my play, I wanted to go further and deeper. The passengers tell their stories to each other as if they’re in a conversation. They examine their individual moral questions and wrestle with their issues. I’m interested in showing how the collective subconscious of imagined lives can change actual lives.

SF: You told me that John Guare, who wrote The House of Blue Leaves and Six Degrees of Separation, said that the audience has an “assignment” when they come to see a play.

KB: He said that when the audience comes to a play, they want to know what the problem is that has to be solved by the end of the performance. They want to go on the journey, care about the characters, feel their emotional stakes and be afraid for them. He called it “the imperative of the audience” and that their “assignment” is to help the characters solve the problem.

SF: What’s your hope for audiences who come to The Coast Starlight?

KB: I hope they feel compelled by each character’s story and exercise their imperative. And that the play has some meaning for them.